On April 26, 1977 -- a long time before superstar D.J.’s, before velvet

ropes, before anyone had ever heard of “club drugs” like XTC, 2CB, and Special K -- Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager let there be light and speed and

spectacle so preternaturally pleasurable that it had to fall apart. But

while the ball lasted, there was no more thrilling nightlife than the

dance on West 54th Street.

These were the days before the tabloid celebrity culture of today, before the predatorial reign of the paparazzi. The world of the "wardrobe malfunction" had yet to become a tired headline. Privacy was still respected by the paparazzi, and people would let loose with wild abandon knowing that what happened at Studio 54, stayed at Studio 54.

Before reality TV allowed everyone and anyone to have their fifteen minutes of fame, revelers would pack Studio, celebrating their place as a Special Attraction by arriving in the buff, or painted silver, or in over-the-top drag. The Freak Flags were flying high.

|

| Rollerena |

|

| Rollerena |

|

| Disco Sally |

|

|

| Divine and Grace Jones |

|

The dance floor was a former stage. Grouped around it were puffy banquettes. Beneath the balconies was the main bar. Ignored by most was a discreet door in the wall that opened onto the stairs that led to the VIP room in the basement. Above were the bleachers, the circle when the place had been a theater, now upholstered (as the joke went) with material that could be hosed down daily. The bleachers were a place for privacy, or as much privacy as one could expect from Studio 54. "You would look around," says David Hamilton, photographer, "and you'd see somebody's back. Then you'd see little toes twinkling behind their ears."

"[Disco music] was the exact antithesis of hippie music that had proceeded it. It wasn't about save the world! It was about get yourself a mate, have fun, and forget about the rest of the world. In a strange way, that was very therapeutic," says Nile Rogers, who became a disco star with Chic and later produced albums for both Madonna and Bowie.

|

| DJ Booth |

|

.jpg) |

| Crow's Nest -- DJ Booth |

|

| DJ Booth |

|

| Diana Ross -- 1980 |

|

| Diana Ross -- 1980 |

THE BEGINNING

Brooklynite Steve Rubell (born 1943) was a young man pursuing a career in restaurant ownership. His first ventures were a place in Bayside, Queens and a fancier place in New Haven, CT called the Tivoli. It was the early 1970s, and what attracted him to the restaurant business was what attracts many amateurs to running restaurants or bars -- the idea that you spend your time not with numbers, but with people.

Fellow Brooklynite Ian Schrager (born 1946) had begun to practice

real estate law in 1974. Steve Rubell approached him and signed him up;

it was Schrager's job to organize a rapidly swelling chain of Rubell's

most recent venture, Steak Loft. Eventually, Schrager came on as a full

partner in ownership.

|

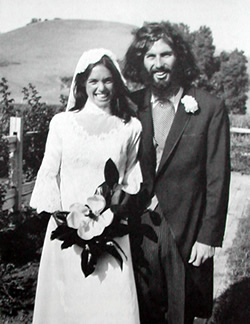

| Ian Schrager, left, and Steve Rubell, right. |

|

|

| Steve Rubell, left, and Ian Schrager, right. |

The two became friends and eventually began exploring the nightworld of NYC together. Schrager was both astonished and impressed by what he saw at the more popular clubs of the time... not just at the size and vigor of the gay culture around him, but at the general mixing and melding of different people, the breaking down of social race and class barriers, and the sight of people willing to stand in line (often in terrible weather for long periods of time) just to have the privilege of getting inside to spend their money. For Rubell, it was party time.

|

| Mid-70s, NYC club ONES in Tribeca |

|

| Mid-70s, line wrapped around the block for NYC club THE BOTTOM LINE |

An inspired Rubell began to throw parties in his own restaurants, and the bulb clicked on for Schrager. He, the lawyer, and Rubell, the restauranteur, would be a perfect combination to enter the nightworld. To others, however, they remained a curious pair. The extroverted gay (Rubell) and the introverted straight (Schrager) would always be social opposites. "In general, Steve stays too long. And I leave too soon," Schrager has said.

Rubell and Schrager began their calculated study of the business, which included a burgeoning relationship with one of the reigning Lords of Nightworld, Maurice Brahms. "Steve could charm your pants off," says Brahms. "You could hate him one day and love him the next. He just had a charm about him. But," he adds, "even when he was stoned, when he used to come in with his mouth open, dribbling from the Quaaludes, he was always watching... always looking... always trying to gather information. There are a few people in the world who are able to function well when stoned out of their minds, and he was one of them. Anybody who thought they could take advantage of him because he was drugged up, they were

wrong."

The duo began with a nightclub in Queens called Enchanted Gardens. Once the two were properly beefed up on the how-to's of Nightworld, it was time to start assembling the essential staff. Carmen D'Alessio, commonly considered to be the first of the Party Promoters, was a true pioneer in a brand-new profession -- celebrity-driven fun. Upon first meeting, the pair decided that she was to work as their PR person. D'Alessio, however, was not convinced. "Of course I told them it was out of the question. I said I have

nothing to do in Queens. I don't know anybody from that part of the world. I don't think I can even bring press there. Why don't you try hiring somebody locally

? I don't know how to help you..." D'Alessio had thought she had seen the last of this on-the-make duo from the unchic Outer Borough wastelands.

|

| Carmen D'Alessio |

|

| Carmen D'Alessio and Andy Warhol @ Studio 54 |

Later, in what D'Alessio realized afterwards was a prearrangement, the duo once again ran into the promoter while dining. "So they appeared," she says. "Really charming, the both of them. They ended up inviting me for dinner. At the end of the night they said 'Would you like to come with us to our Enchanted Garden?' and I said 'Let's go anywhere!'" D'Alessio was ready to get the night started after a long, booze-filled dinner and found herself "amazed that the place was not a dive like I had thought. It was beautiful. So then I decided that I was going to help them. Not as a promoter, because I still insisted that I could not bring them people or press. But I was going to give them themes, plan their parties, so that they could invite their own following of, you know, Queens, or whatever."

D'Alessio's first theme party was the Thousand and One Nights. "I brought Pat Cleveland" -- supermodel du jour -- "and I told them to have camels, real camels, and elephants, and to do the whole trip. The bartenders were sultans, you know, bare-chested, with harem pants and what not. So it was amazing."

Rubell and Schrager grew ever more ambitious. A staff member, Richie Notar, remembers being assigned to ferry a "bald-headed guy... a little chunky" in from Manhattan. Once in costume, this bald-headed guy turned out to be the drag diva, Divine. There was later an appearance by Marilyn Chambers, the former model now spearheading the new trend of Porno Chic by starring in

Behind the Green Door. It was at D'Alessio's instance that Manhattan promoters filled two school buses with celebs and ran them out to the club, in addition to getting Grace Jones to play for free. "I took the von Furstenbergs there

and Calvin Klein," D'Alessio claims. "All this in Queens! The moon!"

It was then that D'Alessio was approached by friends who had spotted an available venue in Midtown Manhattan.

THE BUILDING

The actual building at 254 W. 54th St. was designed to house the San Carlo Opera Company, and it opened its doors in 1927. By 1930, the opera company was gone and the building had became a theater called the New Yorker. Between 1933 and 1936, the premises survived as a cabaret, the Casino de Paris. In 1937, the Federal Music Theater had taken over. Six years later, the building was handed over to the Columbia Broadcasting Company, and for three decades, the space functioned as a soundstage for radio and television. It was here that

Johnny Carson, Beat the Clock, Jack Benny, What's My Line, and

Captain Kangaroo were broadcast into the airwaves. When CBS finally moved to Hollywood, the building was left vacant.

Uva Harden, the man who found Studio 54, was a male German model and had been scouting locations for a disco at which he had been hired to play host. He and his group had scoured the location and determined not only the concept, but even the name.

|

| Uva Harden |

"Because the address was 254 W. 54th St., in a round table discussion somebody threw out the name Studio 54. It was the address. The concept of the studio -- movable sets, the actors being the audience, the audience being the actors -- was mine. No one else's. Unquestionably. A hundred percent," claims Gordon Butler, a member of the founding group.

"I made the name," claims Sidney Beer, another member. "It was on 54th St. I said 'Let's call it Studio 54'. It's a good name. It's easy for people to remember -- where the street is and what the club is. So it's God's truth! I made the name."

Harden and his friends had everything in place but the lease and the liquor license. "We didn't want to sign anything without a liquor license commitment;" says one of the friends, Yoram Polany. "I filled in all the documentation. And for some reason the license just wasn't coming through. I didn't understand why, I just felt like we were getting the runaround."

Bring back in Carmen D'Alessio, the party promoter, who had been invited in for a consultation. "I loved the place from the moment I set eyes on it. I could see the future or something like that. Because up until then, there had been nothing like it in New York. This was the first time I was being shown a theater for a club. And I could already envision that this would be the ideal place for fashion shows and for movie and TV shoots. This could work 24 hours out of 24. This was a winner!"

But yet, the strings were unraveling due to the lack of a liquor license, and major investors were backing out. "Suddenly, with all this going, there was no more investor. And I decided to approach Steve and Ian," says D'Alessio.

D'Alessio took Schrager and Rubell to the old theater. Like so many others, they were daunted by its sheer size. "They asked me, 'Do you think you can fill it"'" D'Alessio says. "And I said 'I will!'"

That was on a Sunday night. By Tuesday or Wednesday of that week, Schrager and Rubell had signed the lease, thus usurping the building from Harden's circle and taking everyone's ideas along with them.

.jpg) |

| Rubell in front of Studio 54 |

Shortly after, D'Alessio brought her attorney in to arrange a partnership with Schrager and Rubell. "They offered her 5% of the net," says D'Alessio's lawyer, Larry Gang.

Net is what a place makes after taxes and expenses and payroll, so you never know what you will end up with as a take-home pay, especially for a new club that might not make it. Gang knew this and hammered out for a percentage of the

gross, which is what the club makes before everything is taken out. "They were good guy, bad guy

," he says. "Steve was the good guy, Ian was the bad guy

. Ian was the one who kept saying 'no no no, we can't offer you that.'"

The bulb clicked on for Gang. These two weren't going to let anyone see what the club made as a gross, before taxes were reported, before expenses were paid. No one was going to see the grand total, because then no one would know exactly how much the club makes aside from Schrager and Rubell themselves. "It was then that I knew they planned on skimming. They planned on skimming from the

beginning," says Gang. He told his client D'Alessio she'd be better off just taking a salary

, which she did.

DESIGN

The disco look was being born. The sheer look of things

was going to be important in the new disco palaces. Some elements were

glitz, such as the humongous emblematic disco ball... Some elements were

gaudy, like the Vegas aesthetic of neon wall art... Other elements were

part of the new technology of special effects, like the strobe light,

borrowed from fashion photography.

|

| One of the many bars at Studio 54 |

Rubell and Schrager

gathered together a team of designers, including an architect, a

florist, and theatrical lighting experts. "Ian was very nervous about

the whole thing and very indecisive," says Scott Bromley, the

architect. "I think we went through four hundred million permutations

and combinations. But I remember walking in to see the space before

meeting Ian or Steve. I said 'this is how it's going to work. Wherever

the floor comes into juxtaposition with the stage, there will either be

a step up or a step down. The stage will be the dance floor,

because everyone has always wanted to be on stage!'"

The

piece de resistance for the club would be the notorious Man In The Moon

electric sculpture. The lead story in the

November 1978 issue of Life magazine was DISCO! HOTTEST TREND IN ENTERTAINMENT by Albert Goldman, and he

described it thusly: "Once every night a surrealistically distended

coke spoon is thrust under the moon's limp schnozz. Cocaine represented

by white bright bubbles goes racing up the elephantine proboscis... The

dancers scream!"

"Getting

in from outside was an experience," says party-goer Pierre Prudhomme.

"You would begin to hear the music... you knew you were in for an

adventure."

The hallway itself acted as a glamorous prologue,

and it was fully exploited for special occasions. One Valentine's Day,

twelve harpists were stationed in the hallway, playing together. Other times, farm animals in realistic pens.

THE OPENING

Next came publicity. Rubell was intent on spreading the word to other club regulars, creating buzz via word-of-mouth alone, when Joanne Horowitz, a secretary at Universal Pictures, approached Rubell. "'Listen! I know where the celebrities are, I get a celebrity

bulletin every day on my desk. Give me invitations and I'll invite the celebrities to the opening.' Steve said 'Great! Let's see what you can do. You do a good job, and we'll sit down and make a more permanent professional arrangement.'"

|

| Jeanne Horowitz, right. |

Rubell then sent Horowitz a bundle of invitations, and she began to scour the schedules of available celebrities.

The Wiz was in production at the time, so Michael Jackson and Diana Ross were in town, as were Henry Winkler and Warren Beatty.

"I sent them all invitations with letters saying this is going the new hot club and blah blah blah," she says.

Opening night, April 26th, 1977, was a night for the history books. Donald Trump and his new wife Ivana showed up, Margaux Hemingway and Cher, Brooke Shields and Robin Leach, in addition to every single one of Horowitz' s movie star guest list. Throngs were waiting outside, pushing towards the doors in a pandemonium. Rubell's intentional word-of-mouth-only tactic combined with the promise of celebrity sightings had worked.

One party-goer, Richard Turley, arrived well after midnight and claims that there were over a thousand people outside. "The place was locked up like a fortress, and we were outside for well over an hour. We were three or four layers back from the doors, and there were thirty or forty layers behind us." He says a doctor in the group started handing out Quaaludes, and the crowd went wild. "There was just as much of a party outside as there was inside!"

Doorman Marc Benecke worked the door opening night. "It was a total, overwhelming experience. Just throngs of people. All these people dressed up, and the drag queens in their incredible costumes."

|

| 19-year-old Marc Benecke chooses from the crowd. |

Neighboring club owner Arthur Weinstein from Hurrah also arrived around midnight, curious about his new rival. As he looked around the spotlit sea of a dancefloor, he realized his club was done for. Everywhere he looked, there were trashed grins, lighted gizmos rising and falling, the spoon making its way to the moon's nose, cheering, black ties, silver face paint, and famous faces coming in and out of focus. "It was pure theater magic," Weinstein says. "Suddenly Steve was on the floor with Bianca Jagger and it was snowing confetti on them. It was like a scene from a movie. I thought 'Holy shit! This is it. I'm destroyed.'"

Needless to say, Jeanne Horowitz, the little secretary from Universal, was subsequently offered a permanent position on the staff of Studio 54.

|

| Schrager, left, and Rubell, right, on opening night. |

Shortly after opening night, Rubell was approached by the reclusive fashion designer Halston to host a birthday party for Bianca Jagger. Florist Renny Reynolds says "We flipped into action to make it happen. I called everybody I knew in New York to come and blow up masses of white balloons. Ian went to arrange for a horse for Jagger to arrive on, and we kept going for three days. We did a drop -- a theatrical drop is a baglike thing that's a folded piece of canvas between bars. You just drop one side and all these balloons flutter down, which was the start of a lot of that. We eventually did Ping Pong balls, confetti, feathers..."

Photos of Jagger riding in on the white horse broke all over the world the following day. "Bianca's party was the catalyst," says doorman Marc Benecke. "It just snowballed from there. That picture started the ball rolling, things happened that quickly for Studio 54."

|

| Bianca Jagger's 30th Birthday Party, 1977 |

THE DOOR

As the club gained popularity in the press, the waiting crowds outside each night grew. Rubell impressed on Benecke the importance of crowd control. "We called it casting a play," says Benecke. "Or tossing a salad. We don't want all tomatoes. When you have a lot of lettuce, you have to mix in other ingredients. Sure, some big tomatoes get in all the time, but you have to include other vegetables, too."

Rubell had an entire philosophy based on the importance of

the look. Occasional doorman Al Corley says that Rubell had a basic line. "'Just make sure you don't let in anyone like me.' Basically what he was saying was, I would not let myself in. It was a joke, but there was a lot of truth to it." Only the fabulous were allowed in, handpicked by the doorman from the sea of people.

Rubell intuitively understood that few things delight the rich and famous, and their courtiers like the press, than getting something for free. Rubell paid his A-Listers literally through the nose because he liked them... and because their presence attracted media attention, and that attention attracted the horde of spectators.

|

| Diane von Furstenberg @ Studio 54 |

|

| Bill Murray and Gilda Radner @ Studio 54 |

A rich folklore soon spread about the Studio door policy. Rubell was very stern regarding what people were wearing. "There was a time I was wearing a particular jacket. A guy comes up and says how can I get in?" remembers Benecke. "I replied 'well, you should go buy this jacket. They have it at Bloomingdale's.' The man returned the next night wearing the jacket, and he still didn't get in! It was amazing to me that anyone would do that. But there was such a fervor, such a need to be inside, to be a part of things."

|

| Rubell manning the door -- 1/06/78 |

|

| Rubell manning the door -- 1/06/78 |

Benecke, of course, could go on and on with the stories of crazed attendees. The newlywed on his honeymoon who left his wife outside in the cold after being told only he could come in. The lady who showed up on horseback dressed as Lady Godiva, only to see her horse be let in for the party while she waited on the sidewalk. The woman who was told she could come in only if she were to strip naked right then and there, which she did, only to be left in the freezing cold until her nipples were literally frostbitten. She was taken to the hospital when the club closed for the night, never having been let in.

"Steve was much more friendly and outgoing with the crowds. He was able to go up to somebody and be buddy-buddy with them while turning them away. I couldn't do that. My thing was not to talk to them. I would just zero in on somebody I knew was going to get in and frankly pretty much ignore those who weren't. And the funny thing was when I would change tactics and say to someone 'I'm really sorry. You don't have a chance. Maybe you should come back another night.' They would just stand there for three or four hours anyway," marvels Benecke.

Michael Musto, now a columnist at

The Village Voice, was one of those just happy to stand there. "Studio had just opened and I thought I would never get in. I was just a kid from Brooklyn! We just stood outside for hours and hours, and that would be a full night's entertainment, just watching the celebrities' limos pull up, and seeing who would come out of them."

THE PARTY

Reporter Dan Dorfman made many visits to the club. "There's never been a place like that for any reporter. How could you not walk out with three stories? There were so many interesting things going on. Forget about the dancing, forget about the excessive drinks, the grass they were selling all over the place, the coke stuffed into the banquettes. Forget about the upper balcony where people were having sex. What really counted was there were so many people there, they were drinking, they were relaxed, and they

talked. It was Storyland! That was what it was. It was

Storyland."

Theme parties began to abound. Studio was turned into a street from Shanghai for the wife of a popular Asian restauranteur's birthday party. It was turned into a barn for Dolly Parton. "We had big wine barrels we filled with corn," says florist Reynolds. "I had a farm wagon that we brought in and piled with hay. We had chickens in a pen. Dolly came in and

completely freaked out at the number of people there. She had not yet had a Studio 54 experience. She was real nervous and went up to the balcony and just sat up there."

|

| Dolly Parton at her Studio 54 party |

|

Reynolds likewise has vivid memories of the premiere party

thrown for the movie

Grease. 1950s-era cars were brought in to decorate the club, and they were just trashed. "There was a 1950 Chevy convertible that had people climbing in, burning up the seats with cigarettes and who knows what else. We had to pay for an entire renovation of the car afterwards. But the party was wild. Fabulous

."

|

| Olivia Newton-John at the Grease! opening party @ Studio 54. |

|

|

Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell acted as both the producer and the director of each night's events. Schrager preferred to stay out of the spotlight and behind-the-scenes, but not Rubell. Nobody whooped it up at the parties more than Rubell, and he was every bit the madcap host. Fueled by Quaaludes and cocaine, Rubell was the life of the party every night.

"When people think of Studio 54, they think of Steve," said Schrager in a 1979 interview with writer Anne Bardach. "Which is perfect for me. I wouldn't be here every night if I didn't have to. Studio 54 is a twenty-four hour job. It's my life. I enjoy it in the shadows. I'm happier with myself. I guess I am the dark side of Steve. This partnership works because have different roles and we like the jobs we do. Steve loves people. I don't, not really."

"Someone once described Steve very well," says his older brother, Don Rubell. "He said that Steve had this ability to perceive fantasies, people's fantasies that they didn't know about themselves. He took people out of their context and put them where they secretly wanted to be, whether they realized it or not. He was able to take people from the real world -- senators, CEOs, celebrities -- and put them into a safe environment where they were able to act out things they had always privately wanted to do."

Rubell, it has been said, hated to be alone. He generated energy and was needy when it wasn't around. Therefore, he surrounded himself with a group of insiders who had an equal appetite for attention. A core group of VIPs began to form, so regular that the public began to know them on a first name basis from the tabloids -- Liza, Andy, Truman, Bianca, Diana, etc. "They were a sort of version of the Rat Pack," says Don Rubell. "Steve was involved with them tremendously."

.jpg) |

| Bianca Jagger and Liza Minelli |

.jpg) |

| Bianca Jagger, Andy Warhol, Jerry Hall, Lorna Luft |

.jpg) |

| Bianca Jagger, Lisa Minelli, Michael Jackson |

.jpg) |

| Bianca Jagger, Andy Warhol, Liza Minelli |

.jpg) |

| Liza Minelli, Truman Capote, Steve Rubell |

|

| Jerry Hall, Andy Warhol, Debbie Harry, Truman Capote, Paloma Picasso |

|

| Bianca Jagger, Liza Minelli |

.jpg) |

| Andy Warhol, Calvin Klein, Brooke Shields, and Steve Rubell |

THE LITTLE BUST

However, legal problems began to crop up almost immediately. Not even a month after opening, Studio 54 experienced its first bust. Scotty Taylor, a bartender, remembers men showing up dressed as cops on May 21st, 1977. He at first assumed they were just in costume for the night. "A guy asked for a drink, and when he was served, he slapped handcuffs on the bartender. These were not dress-up guys, but actual cops from the Midtown precinct, and the were headed by the State Liquor Commissioner, Michael Roth. They started gathering all the bottles from the bar."

Earlier that evening, Roth had been at a dinner when he was asked by a columnist from the

New York Post whether Studio 54 had gotten its liquor license yet. "I said no, they had not," Roth remembers. "The columnist left the table and came back about half an hour, maybe forty-five minutes later, and said 'I was just over at Studio. They've got a big crowd over there and they are selling alcohol. What are you going to do about it?'"

What the embarrassed Roth did was send over cops to buy drinks at Studio, and then had Rubell, Schrager, and two bartenders arrested. "It's beyond me that they would invest all this money into the place and then do that," Albert Yocono of the Department of Consumer Affairs said of Rubell and Schrager's attempt to keep the place going on a one-night-at-a-time catering licenses. "It makes no sense. They didn't have any of the paperwork, they just decided one day to open their doors. They had no certificate of occupancy, no cabaret license, and they don't have a public assembly license. I guess they figure they above the law."

"We'll be open tomorrow night," Rubell promised departing guests. And it was, but sans alcohol.

Ian Schrager admits they knew of the laws and had just decided to ignore them. "We were aware of the law. I

am a lawye

r." His inside knowledge of both the industry and of other clubs similarly breaking the laws worked in his favor. He argued that Studio 54 had been targeted for sensationalism while other clubs were breaking far more aggressive laws, and that the cops chose to ignore them in favor of busting 54. Five months later, in October of 1977

, a judge threw out the case.

Studio 54 was allowed to start serving again, this time with a license.

The next month,

New York magazine published

an article dedicated to the club (and more pointedly, Steve Rubell) entitled THE ECCENTRIC WHIZ BEHIND STUDIO 54. In it, Rubell is quoted as saying "Profits are astronomical. Only the Mafia does better." and "It's a cash business and you have to worry about the IRS. I don't want them to know everything."

Once that article hit the stands, it was widely acknowledged that Rubell had sealed their doom. "Steve was ok, he loved publicity," says the article's author, Dan Dorfman. "But Ian went wild, he went crazy. He just

glowered at me the next time I came in. He said 'I didn't like what you did, I didn't like what you wrote!' and I told him 'Look, this is what he

said.' Steve was very lovable, friendly, he spoke very openly

. How many people would say they make more money than the Mafia? You've got to be out of your mind to make that comment. And it was repeated in a number of papers."

Studio 54's 1977 tax report had declared a gross income of approximately $1 million, and a net taxable income of $47,000. Rubell and Schrager paid altogether $8,000 in taxes. This was not a smart move.

YEAR TWO

The club lost no steam as 1978 dawned. Studio began to get wilder, and it wasn't the typical drunken, snorting, underwear-shedding wildness, either. Neighboring club owner Jim Fouratt explains: "Studio gave license. That was what the door policy was about more than anything else. It was to make you feel that if you got in, you were in a world that was completely safe for you to do whatever you wanted." People would jump from the balconies to grab hold of the illuminated towers that would rise and fall above the floor. Hookers of both genders were arranged at the bar. Freebies of cocaine and Quaaludes were delivered on silver platters to the VIP rooms. The amount of sex happening in the balcony increased with more visibility. "It was the only club where you could have sex," says Egon von Furstenberg. "I had sex with one of my wife's best friends there." Fouratt mentions a supposedly straight magnate who would take boys up to the balcony for quite visible blowjobs. "The fact that he would behave like that in a public place is symbolic of the way that a lot of people behaved."

|

| The cameras and the camaraderie. |

|

| Grace Jones performing. |

|

| Jerry Hall's butt |

|

| Liza Minelli's Birthday -- 1979 |

|

| NYE 1978 |

By the second year, Studio had become so stratified that there was a private door exiting onto a side street, and even a "private" studio, the space behind a scrim on the dance floor that could be raised and lowered at will for more personal parties. The central venue for the inner core was the basement, which had replaced Rubell's first-floor office as the VIP Room. The basement was reached through a door in the wall behind the bar and under the Man in the Moon. You went down grungy cement stairs, holding onto a metal bannister, and found yourself in a wasteland as large as the club itself. The space was separated by cubicles with one main room painted grey, the overhead piping hissing away. The spaces were divided by Cyclone fencing and furnished with destroyed banquettes, rolls of carpeting, and props left over from parties. The beat of the music and the people dancing above roared through the basement. It was not a clean environment, but it was

cool.

|

| Not the basement of Studio 54, but a similar aesthetic. |

It was the posterboard of Reverse Chic, and it was hard to get down there uninvited. Drugs of all kinds were passed, and there were a little room furnished with mattresses for those who were feeling frisky. Bartenders would be whisked down to the mattress room by various women, only to be put on sexual display for the VIP party. One remembers vigorously mounting a star's wife, only to see, mid-performance, that the star in question was looking directly at them without seeming to comprehend what was happening, not caring.

Another bartender recalls "There were four or five rooms down there, one had beds in it, one just had pieces of foam. We would all cover for each other at the bar so we could take turns partying down there. We'd come in, have fun, just pick women at random from the bar who were all so grateful to go down to the VIP room... get drunk, get laid! What the hell, it was perfect! It would happen pretty much every night for some people, sometimes more than once a night."

|

| Studio 54 Busboy / Bartender |

|

| Studio 54 Busboy / Bartender |

One party-goer, Gwynne Rivers, remembers how liberating it felt to be at Studio. "You could dance and even undress if you wanted to with no one giving you any grief about it. It was a very open atmosphere, and you felt very safe, surrounded by all these beautiful people. Everyone was on something, so it would be so fun. You'd be on the dancefloor and somebody would stick something under your nose and you'd become totally gaga. Studio was a fantasyland. A playland for grown-ups. It really was."

The recklessness was extraordinary. "There was a moment in history where everyone preceived that the law was not operable in certain environments. And Studio 54 was one of them, that whatever you did there would not enter the rest of your life," says Don Rubell. "It was do what you will, there was no concept of punishment. The press was very good at never reporting any transgressions. They would say it was a wild party! A great party! But there were no specifics."

The party was getting too fast and too furious. Rubell was surrounded by famous, powerful friends and his drug use escalated to massive quantities each night. Both he and Schrager had come to feel they were inhabitants of a special zone where nothing much could touch them.

|

| Rubell with Mikhail Baryshnikov and Mick Jagger |

|

| Andy Warhol Polaroid, Grace Jones and Steve Rubell |

|

| Steve Rubell, on forefront of floor, white pants |

|

| Steve Rubell, Grease! opening party with Olivia Newton-John and producer Allan Carr |

|

| Steve Rubell with Andy Warhol |

|

| Steve Rubell with Rod Stewart and his wife, Alana |

"I'll tell you, the guy used to do drugs and, oh man, nobody knew how he did it!" says doorman Chris Sullivan. "We all thought he was going to drop. All the bartenders would be finished at the end of the night, and we would have to wait for the manager to bring us down to the basement, where we counted the money. I'm telling you, we made lots of money. I would ring in six or seven thousand dollars at my bar in one night. And that was just my bar! There six, seven, eight bars on a Saturday night, plus the cover charges at the door.

We'd all be down there, counting our money. Steve came down one night. He could hardly stand up. He was 'luded out of his mind. But the guy was amazing, he could add up all the figures. We had to write down each amount, they had a strange system. He was looking over my shoulder, and I was sitting there, trying to add up twenties and crumpled-up ones and stuff. I was just about to start adding, and he said 'Six thousand, three hundred and twenty-two dollars and fifteen cents. Come on, Sullivan!'

He was right on! And he was totally out of it, completely fucked up on whatever he was on. And then he went on. It made me realize, this guy doesn't miss a thing, no matter how high he is. You know, as free and chaotic as the place looked, there was nothing chaotic or free about the way he ran it. The guy didn't put up with any shit. He had an incredible sense of detail."

The staff were always kept young, more than likely to ensure that a lot of business practices would just go right over their heads. The staff didn't wonder, for instance, why a paper shredder was sitting in the main office. Only a very few were aware of the fact that, nightly, after the money and register tapes had been removed from the bar, after the takings from the coat check and cigarette concessions were added, that everything was piled into bank bags which were then packed into a beer crate. The skimmed cash was counted, split, and stowed in such hiding places as behind the basement ceiling panels.

Some who knew of the skim jobs would try to persuade the duo to parlay Studio's success into larger outlets, which would give greater rewards through more legitimate means. They were approached to lend their name to a line of t-shirts, they entertained the ideas of opening a chain of Studios (eventually a Studio 54 would indeed open on the island of St. Thomas in the Bahamas, albeit by a later owner in the 1980s), they even put out a disco compilation record on Casablanca Records. "All sorts of people were always on the telephone to these guys, trying to put together joint ventures," says Ed Gifford, Studio 54 publicist. "They had the nub of an empire, of an entertainment empire.

For several years."

|

| Studio 54 compilation album via Casablanca Records |

They finally accepted a merchandising deal, which came from a Boston clothing wholesaler, Landlubber. The designer jeans business was just beginning to boom and the opportunities were arising. Studio 54 Jeans were created, and the tagline was "Now Everybody Can Get Into Studio 54!" The goods were trucked into stores, and it seemed as if the sky was the limit for the Studio 54 brand.

|

| Studio 54 Jeans ad campaign |

THE BIG BUST

It has always been assumed that it was Dan Dorman's

New York magazine article that so enraged the feds, pushing them to raid the club, but it was actually an inside job. Donald Moon, a former employee of Studio, had fallen afoul of Rubell and had been quickly dismissed. "Steve wasn't very tactful about getting rid of people," Studio 54 partner Jack Dushey says. "He fired him. The guy didn't like it." He disliked it enough to call the feds.

Moon's only motivation seemed to be burning rage. He didn't ask for rewards, all he asked was to disappear into the federal witness program. This was granted, and he told the IRS about a secret safe with the double set of books. He told of the trash bags of treasure hidden in the basement ceilings. He told of a lot of things.

Speedily, a task force was put together and a search warrant granted. The first group of raiders arrived at 9:30am on December 14th, 1978, and they went straight down to the basement. They took both sets of books, knowing exactly where they were hidden, in addition to the bags of hidden cash -- nearly a million dollar's worth which had been gathered over the course of only a few nights. Rubell was caught in his car and a further $100,000 was found in the trunk. Other agents went to his apartment and grabbed the cash hidden behind his bookshelves.

|

| Rubell's Nightly Guest List |

|

| Rubell's Nightly Guest List, with coding for freebies and whether they paid for anything |

Halfway through the raid, Schrager showed up, carrying books which had several packages of cocaine inserted between the pages. Schrager was arrested for possession with intent to distribute.

Studio opened that night regardless of the raid. "When you are in the public eye, you expect to be harassed," said Rubell to

The Washington Post. He let it be known that the night of the raid had been the biggest weekday turnout in the club's history.

.jpg) |

| Schrager and Rubell with their lawyer, Roy Cohn |

.jpg) |

| Schrager, left, and Rubell, right, with Studio 54's lawyer Roy Cohn |

The feds could not believe the balls on the pair, even when in questioning. "At our first debriefing, I asked Steve 'Would I get into Studio 54?'" remembers Peter Sudler, the Assistant US Attorney who was handling the case. "He looked at me, he had this little smile. He said 'No. You're one of the gray people.' I was in my office, I thought the agents were going to fall on the floor. I thought this is unbelievable. What chutzpah!"

The fed debriefings continued. "They came up with all these crazy stories -- real cockamamy stories -- to explain the money and the second set of books. They came up with this story that they had been hoarding to pay for renovations," Sudler says. They worked up a defense in which chaotic bookkeeping would figure in rather than downright villainy. This yarn lasted until the IRS found detailed records of the split, along with $900,000 cash in a safe-deposit box at the Citibank at 640 Fifth Ave.

Rubell and Schrager plea-bargained for several months. At the end of June 1979, they were charged with skimming $2.5 million. Studio fever remained unabated, regardless. Requests for private parties were so voluminous that additional party planners had to be hired. People went crazy for the danger, and longed to be associated with it. Favored celebrities continued to show their loyalty to Rubell by arriving nightly.

|

| Rubell with his laywer Roy Cohn outside the courtroom in 1979 |

THE AFTERMATH

That all collapsed in the first week of November 1979.

New York magazine published a cover story entitled STUDIO 54: THE PARTY'S OVER. In this story, details were published for the first time of the debauchery that went on beyond the velvet rope. A list of "party favors" was produced, which detailed all the little presents -- mostly cocaine and poppers -- slipped into the palms or pockets of Rubell's famous friends, along with a monetary value of the freebie.

The famous were shocked at finding themselves on the list, which was less at seeing their habits exposed than at finding themselves listed as business expenses by Rubell and Schrager. No one was more shocked than Rubell, who asked friends why the author would print such things, considering he had been treated so nicely on his visits to the club. "He perhaps broke the privacy code, but you allowed him to see all of this. He really hasn't said anything that wasn't true," said neighboring club owner Jim Fouratt to Rubell.

Rubell and Schrager, beginning to feel the waves of a social shunning, approached US Attorney Peter Sudler and agreed to plead guilty and to cooperate with other investigations against neighboring clubs. The cooperation would consist of information against other potential targets, and they compiled a list of fellow clubowners who had also been skimming the books.

It was simple enough to the feds. "What was curious about Studio 54 was the size of the money they took. They were really greedy," says Sudler. "Normally, if people skim from a cash business, they'll skim ten or fifteen percent, maybe twenty-five percent at the most. These guys skimmed five million dollars in one year, probably eighty percent of their gross. It was ridiculous!"

Schrager agrees. "You get intoxicated with your success. We had gone wrong. We had realized it was ridiculous, we were on a self-destruction course."

Rubell later said "I used to have dinner at my parents' house every week, I thought I was the same old guy. I didn't realize I had lost my way, I never thought I was hurting anybody. I enjoyed it so much, every day I looked forward to the night. But I was like a permissive parent. I let everybody do whatever they wanted, and I paid the price."

Rubell and Schrager were found guilty on January 18th, 1980, and were sentenced to three and a half years in

prison and a $20,000 fine each for the tax evasion charge. They threw one final party, which was emotional and fairly small, nothing like the rambunctious affairs of New Year's Eve past, where four tons of glitter fell onto the floor from the ceiling. "We had arrived late that night," says gossip columnist Jack Martin. "The crowd had already started to thin out and the festivities were over. Steve was sort of alone, there was nobody else with him but me and my guests for the next four, five, six hours, however long we sat with him. He was sort of spaced-out. He had accepted it. It was a sad going-away party but were laughing and trying to have fun. We were with him literally until he took a car to go home and meet the authorities."

Studio 54 was over.

On February

4th, 1980, Rubell and Schrager went to prison. Studio's liquor license expired on February 28th, 1979 and officially closed in March.

Doorman Marc Benecke remembers the fallout. "It was kind of like being on tour with the Rolling Stones for three years straight. And then it was...

over. There was this great whirlwind, and it just stopped. It was very difficult, I went through a terrible period of self-doubt. You find out who your friends really are. The invitations stop coming, you get a lot less cards at Christmas, people don't recognize you anymore. Stuff like that."

THE FUTURE OF 54

Studio 54 was sold in

November of that year for $4.75 million to a man named Mark Fleischman. On January 21st, 1981, Rubell and

Schrager were released from prison after handing over the names of other

club owners involved in tax evasion. As part of the deal from the sale of the club, they were hired on by the new Studio owner to act as consultants over the aesthetic policy and the staff.

Life after Studio proved to be difficult at first. There was no money, as the lawyers and the government had seized everything. The reaction of Rubell's host of famous friends was interesting -- some were still upset about the published Party Favors list. Diane von Furstenberg and Andy Warhol refused to maintain a friendship. Others were supportive, such as Calvin Klein who provided the two with a blank check to start over. A majority of others chose to turn moralist, which shocked the pair.

"Nobody wanted to know Rubell when he got out of jail," says the writer Dotson Rader. "It was a said sight. It was as if all of a sudden everyone moved away from his table. A lot of people with the social lubricant of Studio 54, the feeling of safety, the high of the drugs, they behaved in ways that were not part of their identity. It was completely safe. They they got busted, and no one felt safe with them anymore."

Rubell himself said "You get out, you're elated. You feel you've paid the price. A few weeks later, you realize you have to start all over again. People have moved on, and you're alone. I went into a four-month depression. Coming home was harder than being in jail."

During the year and a half that Studio had remained closed, the culture of the Nightworld had shifted. The innocence was gone, and glitz was over. There were new clubs popping up, anti-disco scenes were prevailing, and the hours of the night were getting later and later.

While Rubell and Schrager stayed on to guide the newly re-opened Studio 54, the essence had changed and the magic was gone. They began to collaborate with other new clubs to capitalize on the current trends for party people. Disco was dead, and the downtown art scene was moving in. Studio 54 re-opened after an extensive makeover on September 12th, 1981, with the former owners staying on for six months total. Even with their guidance, the club struggled to attract the same crowd.

"In the early days of disco, it was such a drug-oriented thing, party supplies abound," said the new owner Fleischman. "People were going to discos for a party. I think that started to slow down. The drugs were changing, and the law was starting to crack down. It became harder for people to have the energy to go out every single night of the week the way they used to in the late seventies. All of sudden people were either cleaning up their acts or falling further down the rabbit hole. They just weren't fueled by coke every night. This was the 80s. There wasn't that sense of voyeurism and exhibitionism, everyone was starting to crash."

There was now a concerted effort to attract the very customers that Rubell and Benecke had been most keen to keep out, just to keep the place filled. The bubble of exclusivity had burst. While the club continued to make money by bringing in a slew of different party promoters, who would each arrive with their own different scenes, it was no longer familiar territory to the ghosts of Studio's past.

Manhattan was filled with former Studio celebs going through acute cases of limelight deprivation, if not freebie withdrawal. "People like Bianca Jagger just didn't get it," says promoter Baird Jones. "They kept showing up and they looked like beached sea monsters. The tide had run out, and they looked so peculiar. They would always go downstairs to the basement first, and the basement wasn't happening, so they'd wander up to the office. They would just show up, and Benecke would be apologizing to them, telling them they were mistaken for coming, that it wasn't the same. I mean, the crowd was younger than before, it wasn't glamorous, it wasn't shrouded in safety, it was just another club now." Studio 54 eventually closed its' doors for good in March of 1986 due to insurance woes. It never managed to regain its former glory.

Long before then, Rubell and Schrager had receded from Studio 54, where they had been relegated to background figures. This mattered little to Rubell and Schrager, who had already made moves towards a different comeback trail. Quietly having purchased the Executive Hotel on Madison Avenue, they renovated the building and renamed it Morgan's, which successfully opened on October 1st, 1984.

|

| The Morgans before (inset) and after, 1984 |

|

| Rubell, left, and Schrager, right, at the opening of The Morgans in 1984 |

|

| Rubell and Schrager inside The Morgans |

Rubell later opened the Palladium in 1985, a large dance club famous for displaying art by Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kenny Scharf and Andy Warhol. His new club also quickly rose to fame and was considered central to the New York club scene in the 1980s. This time around, however, the party was just business for Rubell. Gone were the days of being the center of attention, and it became rare to see him in the more public parts of Palladium. He preferred to remain out of the spotlight, essentially having graduated into a more intimate scene.

|

| The Palladium, exterior |

|

| The Palladium, interior |

|

|

| Jean Michel-Basquiat and his work |

|

| Keith Haring and his work |

|

| Kenny Scharf and his work |

Schrager and Rubell continued to grow their hotel empire, buying up other hotels and developing condominiums. Schrager would go on to become a hotel magnate, creating the concept of the "boutique hotel" and further finding success in real estate development.

Rubell, however, was not as fortunate. Having tested positive for AIDS in 1985, Rubell had done little to care for his fragile system. Still a workaholic, still ingesting copious amounts of drugs, still running on very little sleep, Rubell fell gravely ill in June of 1989.

"I think Ian felt very guilty," says Rubell's longtime partner, Bill Hamilton. "Why would one of them get sick and not the other? The two of them were out just as much, even if by now they were running with different communities." In the last weeks of his life, Rubell's appearance deteriorated with shocking speed. He grew thin and his hair grew thinner, and he eventually refused to be seen out in public at all. This was at the height of the AIDS crisis, and gossip ran wild about the health of New York's most influential nightlord.

Rubell was eventually checked in to Beth Israel hospital on July 23rd, 1989. He died two days later, on July 25th, 1989. Beside him were Hamilton, Schrager, and his brother Don Rubell.

THE LEGACY

"Studio 54 really changed everybody's life in a substantial way," says writer Steven Gaines. "It changed eating habits, sleeping habits, drug habits. I mean, the Hamptons were empty on Sunday nights because Studio 54 was the most important place you could be. Every night, for that matter. It was the center of the universe."

The heyday of Studio 54 was brief and luminous, and it is perhaps because of this brevity and brightness that the club seems suspended in time. Studio had been both an implosion and an explosion, the culmination of some very 1960s notions of freedom, openness, giddy display, hope. Sex was good for you and more sex was better, and cocaine was believed to be a non-addictive pick-me up, much easier on the system than booze and champagne.

Studio single-handedly boosted tabloid culture into what we know it as today. Tangible celebrity worship began on that dancefloor and was shared with the public en masse. Studio also single-handedly changed the way nightclubs operated in New York City -- the way you drew people in, the sense of communal exclusivity, what was allowed, and what eventually wasn't allowed. The birth of the big club began on that fateful night in April of 1977.

"Studio 54 changed our life. And then Morgan's changed our life," Schrager told a reporter in the early summer of 1988. "Jail changed our life," Rubell added.

Ian Schrager may have summed it up best: "The place really exploded. It was like a meteor that just crossed the sky, but it was cursed. It crashed, and it took everybody that was involved with it."

|

| Rubell 1977 |

|

| Rubell within Studio 54 |

|

| Rollerena today |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)