Cleopatra may be one of the most recognizable figures in history but we have little idea of what she actually looked like. Once conquered, an enemy's images were erased from the daily lives of our ancient counterparts; only a few remaining marble and stone busts can be viewed as potential likenesses. Countless modern interpretations have been painted with many liberties taken. Therefore, her coin portraits -- issued in her lifetime, and of which she likely approved -- can be viewed as one of the only forms of likeness authenticity. These coins paint her with a hooked nose, full lips, a sharp and prominent chin, and a high brow with wide and sunken eyes.

We remember her, as well, for the wrong reasons. A capable, clear-eyed sovereign, she knew how to build a fleet, suppress an insurrection, control a currency, alleviate a famine. She was the sole female of the ancient world to rule alone and to play a role in Western affairs. She was incomparably richer than anyone else in the Mediterranean, and she enjoyed greater prestige than any other woman of her age. She nonetheless survives as a seductive temptress.

The literary resources available to scholars today are extraordinarily skewered. As we all know, history is written by the winners, and unfortunately, Cleopatra ended up as a loser. Therefore, most surviving accounts deliver up the tabloid version of our Egyptian queen -- insatiable, treacherous, bloodthirsty, power-crazed. Add to that a very limited bank of resources... No papyri from Alexandria survive. Almost nothing of the ancient city survives above ground. We have only one written word of Cleopatra's in existence. Piecing together a true and unbiased biography would prove to be exceptionally difficult.

But this we do know:

She grew up amid unsurpassed luxury, to inherit a kingdom in decline. For ten generations her family had styled themselves pharaohs. The Ptolemies were in fact Macedonian Greek, which makes Cleopatra approximately as Egyptian as Elizabeth Taylor. The word "honey-skinned" recurs in descriptions of her family, which would have undoubtedly been true for her, as well. At age eighteen, Cleopatra and her ten-year-old brother assumed control of a country with a weighty past and a wobbly future. 1300 years separate Cleopatra from Nefertiti. The pyramids already sported graffiti. Cleopatra's family ruled a country that even in the ancient world was steeped in antiquity. She came of age in a world shadowed by Rome, which had extended its rule to Egypt's borders.

Because of her standing, she would have been afforded an excellent education. Not just in literature and science, but in discourse and communication, posture and mannerisms. It has been noted that Cleopatra was instructed as to where to breathe, pause, gesticulate, pick up her pace, lower or raise her voice. She was to stand erect. She was not to twiddle her thumbs. It was the kind of education that could be guaranteed to produce a vivid, persuasive speaker... as well as to provide that speaker with an ample opportunity to display her skill in wit and charm. This was all well and good, as hers was an oral culture, and Cleopatra knew how to talk. Even her naysayers gave her high marks for her language and presentation. Each time her "sparkling eyes" are mentioned in antiquity, equal tribute is paid to her eloquence and charisma. She reportedly had a rich, velvety voice, a commanding presence, and a knack for engaging an audience.

Another benefit of her education allowed her to be fluent in a reported nine different languages. "It is a pleasure merely to hear the sound of her voice," notes Plutarch (born 75 years after the death of Cleopatra), "with which, like an instrument of many strings, she could pass from one language to another; so that there were few of the barbarian nations that she answered by an interpreter; to most of them she spoke directly." [Life of Antony (XXVII)] She was allegedly the first and only Ptolemy to bother to learn the native language of the 7 million people of which she was the ruler.

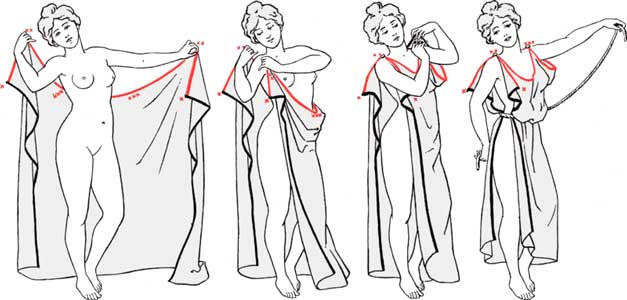

As for how she looked, most theories are pure conjecture backed by ancient descriptions of dress and archaeological findings of adornment. For the most part, she would have been dressed in a fashion common to most Egyptian women: fully clothed in a formfitting, sleeveless, long linen tunic. Her accessories would have covered a wide range of formality and dazzle, but the only accessory she required was the one she alone among Egyptian women could wear... the diadem, or broad white ribbon, that denoted a Hellenistic ruler. It would have been almost permanently tied around her forehead and knotted at the back.

The ancient world was no stranger to singing the praises of great beauties -- Helen of Troy, Arsinoe II, Alexander the Great's mother. But Cleopatra has only been described as having beauty that, according to Plutarch, "was not in itself so remarkable that none could be compared with her, or that no one could see her without being struck by it... [rather] the contact of her presence, if you lived with her, that was irresistible." It would appear that Cleopatra was a woman of average looks but incredible charm. Luckily for her, beauty can only get you so far... but charm can get you everywhere.

There is no trace of the wardrobe she would have regularly worn, but it is known that she donned plenty of pearls, considered to be the diamonds of her day. She would coil long robes of pearls around her neck and would braid more into her hair (often styled into rows of rolls, called the "melon" look of the Hellenistic age).

She would have even more pearls sewn into the fabric of her tunics, which weren't always made of gauzy linen. They would all be ankle-length in a variety of colors (Alexandrian women loved color), but would often be composed of Chinese silk. Traditionally, this would be worn belted, or with a brooch or ribbon. Over the tunic would be placed a transparent mantle (thin cloak), and on her feet would be jeweled sandals with patterned soles.

Pearls aside, Egyptian taste ran to the colorful semiprecious stones, which would be set in gold pendants, bracelets, and long dangling earrings. Agate, lapis, amethysts, carnelian, garnet, malachite, topaz -- all bright gemstones of the time that have been found amongst the archaeological relics of Egypt's Hellenistic period.

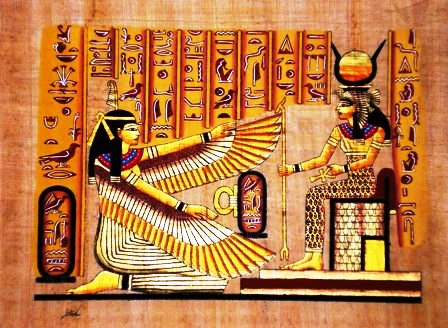

As her reign progressed, Cleopatra began to incorporate the image of Isis, one of the earliest and most important Egyptian goddesses, into her public persona. Isis represented motherhood, enchantment, the wind, and science. An intelligent and charming caretaker, very much in line with Cleopatra herself. On ceremonial occasions, she would assume the guise of Isis, appearing in a full and finely pleated linen mantle of iridescent stripes, fringed at the bottom, tightly wrapped from hip to left shoulder and knotted between the breasts. Under it would be a snug Greek sheath (a "chiton").

On her head she would wear her diadem. For religious events, a traditional pharaonic crown would be donned of feathers, solar disk, and cow's horns.

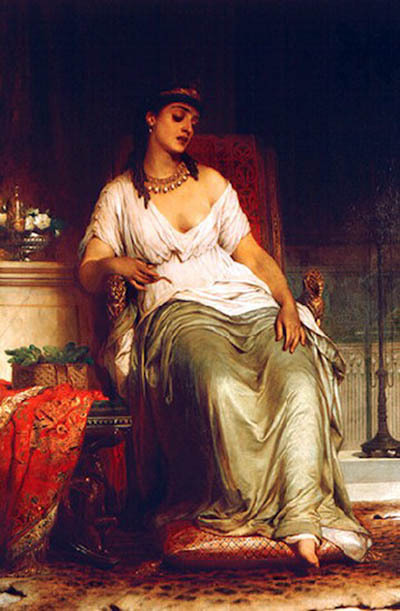

Most contemporary portraits portray Cleopatra in a rather romantic pose, breast exposed (tellingly enough), either lounging or standing on display. She is often confused with the Christian myth of Eve in portraiture, heavily styled with a snake. However, Cleopatra did not die of a snake bite, as touted by Augustus Octavian after her defeat, but rather presumably by a tested poison that had been smuggled to her in a basket of figs.

Unfortunately, facts do not make for good art, and the fantasy rages on throughout time. Cleopatra the Temptress, Cleopatra the Wily Woman, Cleopatra the Egyptian Phenomenon.

For more interesting Cleopatra confusion in art history, visit Painting Histories, an excellent side-by-side comparison of the various ways the queen has been re-imagined.

For further reading, please explore "Cleopatra -- A Life" by Stacy Schiff.

|

| How the Queen of Egypt chose to be portrayed to her people -- 80-drachma bronze, Hunterian Museum (Glasgow) |

|

| Silver tetradrachm of 36 BC, minted in Antioch, announcing Antony (right) and Cleopatra's (left) alliance. |

|

| Bronze coin of 47 or 46 BC, minted in Cyprus, to commemorate the birth of Caesarion (father Julius Caesar). |

We remember her, as well, for the wrong reasons. A capable, clear-eyed sovereign, she knew how to build a fleet, suppress an insurrection, control a currency, alleviate a famine. She was the sole female of the ancient world to rule alone and to play a role in Western affairs. She was incomparably richer than anyone else in the Mediterranean, and she enjoyed greater prestige than any other woman of her age. She nonetheless survives as a seductive temptress.

The literary resources available to scholars today are extraordinarily skewered. As we all know, history is written by the winners, and unfortunately, Cleopatra ended up as a loser. Therefore, most surviving accounts deliver up the tabloid version of our Egyptian queen -- insatiable, treacherous, bloodthirsty, power-crazed. Add to that a very limited bank of resources... No papyri from Alexandria survive. Almost nothing of the ancient city survives above ground. We have only one written word of Cleopatra's in existence. Piecing together a true and unbiased biography would prove to be exceptionally difficult.

| |

| Underwater ruins of Cleopatra's castle -- Bay of Alexandria, Egypt |

|

| Underwater ruins of Cleopatra's castle -- Bay of Alexandria, Egypt |

But this we do know:

She grew up amid unsurpassed luxury, to inherit a kingdom in decline. For ten generations her family had styled themselves pharaohs. The Ptolemies were in fact Macedonian Greek, which makes Cleopatra approximately as Egyptian as Elizabeth Taylor. The word "honey-skinned" recurs in descriptions of her family, which would have undoubtedly been true for her, as well. At age eighteen, Cleopatra and her ten-year-old brother assumed control of a country with a weighty past and a wobbly future. 1300 years separate Cleopatra from Nefertiti. The pyramids already sported graffiti. Cleopatra's family ruled a country that even in the ancient world was steeped in antiquity. She came of age in a world shadowed by Rome, which had extended its rule to Egypt's borders.

| |

| Relief of Cleopatra (wearing Isis headdress, left) and her son Caesarion (father Julius Caesar) at the Temple of Dendera |

|

| Temple of Dendura, Egypt |

Because of her standing, she would have been afforded an excellent education. Not just in literature and science, but in discourse and communication, posture and mannerisms. It has been noted that Cleopatra was instructed as to where to breathe, pause, gesticulate, pick up her pace, lower or raise her voice. She was to stand erect. She was not to twiddle her thumbs. It was the kind of education that could be guaranteed to produce a vivid, persuasive speaker... as well as to provide that speaker with an ample opportunity to display her skill in wit and charm. This was all well and good, as hers was an oral culture, and Cleopatra knew how to talk. Even her naysayers gave her high marks for her language and presentation. Each time her "sparkling eyes" are mentioned in antiquity, equal tribute is paid to her eloquence and charisma. She reportedly had a rich, velvety voice, a commanding presence, and a knack for engaging an audience.

Another benefit of her education allowed her to be fluent in a reported nine different languages. "It is a pleasure merely to hear the sound of her voice," notes Plutarch (born 75 years after the death of Cleopatra), "with which, like an instrument of many strings, she could pass from one language to another; so that there were few of the barbarian nations that she answered by an interpreter; to most of them she spoke directly." [Life of Antony (XXVII)] She was allegedly the first and only Ptolemy to bother to learn the native language of the 7 million people of which she was the ruler.

As for how she looked, most theories are pure conjecture backed by ancient descriptions of dress and archaeological findings of adornment. For the most part, she would have been dressed in a fashion common to most Egyptian women: fully clothed in a formfitting, sleeveless, long linen tunic. Her accessories would have covered a wide range of formality and dazzle, but the only accessory she required was the one she alone among Egyptian women could wear... the diadem, or broad white ribbon, that denoted a Hellenistic ruler. It would have been almost permanently tied around her forehead and knotted at the back.

|

| Cover of "Cleopatra -- A Life" by Stacy Schiff |

The ancient world was no stranger to singing the praises of great beauties -- Helen of Troy, Arsinoe II, Alexander the Great's mother. But Cleopatra has only been described as having beauty that, according to Plutarch, "was not in itself so remarkable that none could be compared with her, or that no one could see her without being struck by it... [rather] the contact of her presence, if you lived with her, that was irresistible." It would appear that Cleopatra was a woman of average looks but incredible charm. Luckily for her, beauty can only get you so far... but charm can get you everywhere.

There is no trace of the wardrobe she would have regularly worn, but it is known that she donned plenty of pearls, considered to be the diamonds of her day. She would coil long robes of pearls around her neck and would braid more into her hair (often styled into rows of rolls, called the "melon" look of the Hellenistic age).

|

| Marble bust, said to be one of the ladies of Cleopatra VII's court who went with her to Rome in 46 BC -- Italy 80-40 BC. London, British Museum. |

She would have even more pearls sewn into the fabric of her tunics, which weren't always made of gauzy linen. They would all be ankle-length in a variety of colors (Alexandrian women loved color), but would often be composed of Chinese silk. Traditionally, this would be worn belted, or with a brooch or ribbon. Over the tunic would be placed a transparent mantle (thin cloak), and on her feet would be jeweled sandals with patterned soles.

Pearls aside, Egyptian taste ran to the colorful semiprecious stones, which would be set in gold pendants, bracelets, and long dangling earrings. Agate, lapis, amethysts, carnelian, garnet, malachite, topaz -- all bright gemstones of the time that have been found amongst the archaeological relics of Egypt's Hellenistic period.

|

| Seal rings, Metropolitan Museum NYC |

|

| British Museum, London |

|

| Metropolitan Museum, NYC |

As her reign progressed, Cleopatra began to incorporate the image of Isis, one of the earliest and most important Egyptian goddesses, into her public persona. Isis represented motherhood, enchantment, the wind, and science. An intelligent and charming caretaker, very much in line with Cleopatra herself. On ceremonial occasions, she would assume the guise of Isis, appearing in a full and finely pleated linen mantle of iridescent stripes, fringed at the bottom, tightly wrapped from hip to left shoulder and knotted between the breasts. Under it would be a snug Greek sheath (a "chiton").

| ||

|

On her head she would wear her diadem. For religious events, a traditional pharaonic crown would be donned of feathers, solar disk, and cow's horns.

| ||

| Contemporary re-imagining of Isis headdress |

|

| Egyptian papyrus of goddesses Ma'at (left) and Isis (right) |

Most contemporary portraits portray Cleopatra in a rather romantic pose, breast exposed (tellingly enough), either lounging or standing on display. She is often confused with the Christian myth of Eve in portraiture, heavily styled with a snake. However, Cleopatra did not die of a snake bite, as touted by Augustus Octavian after her defeat, but rather presumably by a tested poison that had been smuggled to her in a basket of figs.

Unfortunately, facts do not make for good art, and the fantasy rages on throughout time. Cleopatra the Temptress, Cleopatra the Wily Woman, Cleopatra the Egyptian Phenomenon.

| ||||

| "The Death of Cleopatra" -- Jean Andre Rixens, 1874, Musée des Augustins de Toulouse | (France) |

| ||

| "Cleopatra Before Caesar" -- Jean-Leon Gerome, 1866, lost. |

| |||

| "Cleopatra" -- Thomas Francis Dicksee, 1876, lost. |

|

| "Cleopatra" -- J.W. Waterhouse, 1888, private collection |

For more interesting Cleopatra confusion in art history, visit Painting Histories, an excellent side-by-side comparison of the various ways the queen has been re-imagined.

For further reading, please explore "Cleopatra -- A Life" by Stacy Schiff.